Lights, camera, brainstorm! – Doing science in full view in a global pandemic

By Keith Devlin @profkeithdevlin

I had been looking forward to attending the Joint Mathematics Meetings in Seattle early this month. I had attended every JMM since I moved to the US in 1987, and missed not being able to meet up with my many friends and colleagues last year, when the coronavirus pandemic led to the cancellation of the January 2021 meeting as an in-person event.

But it was not to be. On December 22, the AMS announced that they had reluctantly decided to cancel this year’s in-person meeting as well.

In fact, I’d already decided to pull out five days earlier; on December 17, I emailed the members of the American Institute of Mathematics Advisory Board, which I chair, to tell them I would miss the upcoming meeting.

Up until then, I felt perfectly comfortable attending; I had received my third mRNA vaccine shot back in September when it first became available to me, and soon afterwards attended an AIM lecture and open-air social event at Santa Clara University, where vaccination and masking indoors were required. Everything went smoothly and it was good to re-connect again. As long as I was careful, the JMM would be fine, I told myself. I booked my airplane flights to Seattle and my hotel room at the Conference Center, bought two home COVID-testing kits to check myself before returning home, and set up the JMM vaccination-passport app on my iPhone to allow me access to the meetings facilities.

Sure, there was still a risk, but as someone who regularly rides road and mountain bikes, and in the past was a rock climber (at the VS and occasionally HVS level), I’ve always accepted risks that may be slightly elevated above those of driving, flying, taking a shower, and eating meat, provided the payoff in terms of quality of life was worth it.

So what changed my position? Of course, as I write these words, everyone knows the answer: the Omicron variant of the virus. But why did I change my assessment of the risk a few days before the AMS (or most other people) did?

The answer involves what for me has been a fascinating, two-years-long learning experience the pandemic has afforded anyone with a Twitter account. Read on.

From the very early days of the epidemic, before the novel coronavirus hit our shores, a number of leading epidemiologists started using Twitter to circulate, comment on, and discuss the latest information as soon as it was available, including posting summaries of, and links to, their own most recent research findings, and those of their institutions. Those posts were, of course, written with a deliberate public outreach purpose – why else Twitter – but the exchanges they had with other experts were also an integral part of the global research process. As a result, interested outside observers (as I am) were able to follow the science as it was emerging, “worts-and-all.”

Now, for all I know, those scientists had been using Twitter that way for years. I only came across their posts (often lengthy threads of 25 or more graph- and chart-filled tweets) because I started looking for coronavirus information, both to guide my personal actions during the unfolding crisis, and to comment on the mathematical aspects of understanding and dealing with the virus on Devlin’s Angle, and through my other blogs and outlets. What I found was fascinating, and very relevant to my “day job” as a mathematician with a particular interest in mathematical thinking.

[I published a lengthy article on what I mean by the term “mathematical thinking” on Devlin’s Angle in September 2012, timed to coincide with the launch of my Stanford online course (MOOC) Introduction to Mathematical Thinking on Coursera and the publication of a small paperback and an e-book with same title.]

The way epidemiologists use mathematics provides a superb example of mathematical thinking. In fact, well over than half the articles I have posted on this blog since the start of the pandemic have been about mathematical thinking as exemplified by the way epidemiologists use it. The reason is simple: understanding and managing an epidemic, and even more so a global pandemic, is a perfect example of a wicked problem, the topic of last month’s post.

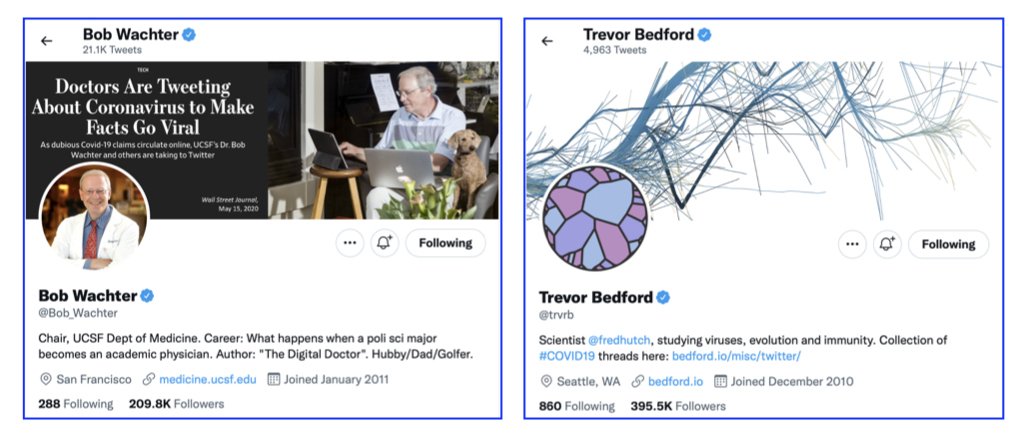

Of the many (highly qualified) experts posting about COVID-19 on Twitter, there were five I have found particularly informative, not just in terms of my own understanding of the pandemic as it affects me, but as a connoisseur of mathematical thinking applied to a wicked problem. You will find screenshots of their Twitter profiles scattered below.

Twitter bios of two of my favorite epidemiology experts, who regularly share emerging scientific data, provide their expert opinions on how the new information affects all of us, and provide us all a front-row view as they discuss and debate the latest results

Of the five, UCSF’s Dr Bob Wachter provides perhaps the most accessible posts. In his longer threads in particular, he often sets his sights clearly on providing public information, generally relying on links within the tweets (usually to articles or to tweets and threads from other experts) to take readers to the more scientific details his arguments are based on, but which he judges many would not wish to see. The 25-tweet thread he posted on December 17 was of that nature, and that was the one that persuaded me to cancel my Seattle trip, which I did later that very day.

I reproduce below the argument he presented. To make for smoother reading, I have reformatted the thread into a single passage, and at the same time removed some abbreviations and cleaned up a few typos. You can read the thread in its original form by following the link above. (This particular thread has no specific pointers to the many sources of his information on which he based his argument. You’ll likely understand why he presented it that way when you see what he says.)

START OF THREAD

This is one of the most confusing times of the pandemic, with a firehose of new Omicron data (lots of fabulous work on #medtwitter putting it into context). In this (long) thread, I'll offer my take on how the new information is changing my thinking & behavior.

I'll start with a few general principles & observations (to save space & time I’m largely going to omit primary data – it’s out there; follow @EricTopol to keep up):

1) Things are uber-dynamic. We have far more clarity now than we had 3 weeks ago, but many unknowns remain. More infectious: yes, but I’m not sure by how much. Immune evasion: definitely. Severity: conflicting data from UK & South Africa, even today. Could mean it's same as Delta, could mean it's moderately less. I doubt it's more severe or massively less severe. We'll learn more soon.

2) If you’re looking for “this is safe” or “this is unsafe” advice, you won't get it here – the situation is too nuanced for that. There’s safER & LESS safe. And context matters: what might be safe for a healthy 30-year-old could be way too unsafe for a frail octogenarian.

3) It’s not about you alone. That healthy 30-year-old can spread Covid unwittingly to someone at high risk, including a loved one. So, decisions about risk need to account for risk to others.

4) We’re all exhausted and sick of living this bizarre and diminished life. Quite naturally, this will influence many people’s decision-making and risk tolerance. But it doesn’t change the risks of those choices one iota. The virus is chipper and ready to go. It continues to deserve our respect, and appropriate caution based on the science.

5) Speaking of calibrating behavior, a few months ago, I shifted my attitude – Covid will be with us for the long haul, & thus I was personally more comfortable taking calculated risks (i.e., visiting family over holidays), in part because “if not now, when?” In other words, in my risk/benefit calculation, I removed my “Remain Extra Careful; Covid Will Go Away” temporal factor. But now, w/ Omicron cases skyrocketing, I’ve added back that "hunker down" variable – I see the next few months as a time to fortify one's safety behaviors. Why?

First, Omicron looks to have peaked in South Africa; we'll likely see a familiar surge-then-plunge pattern, just with a much steeper upslope. Second, I’m quite worried about an overwhelmed healthcare system – we’ll rapidly hit capacity limits in meds, beds, ICUs, testing, and most importantly people (many MDs/RNs out sick too). Trust me, you want to avoid getting sick when the system is stressed. Third, I see the Pfizer oral anti-viral as a very big deal, and it won’t be available for 4-6 weeks (even then it'll be in short supply).

6) Hunkering down means trying to limit risky activities. We now appreciate the negative impact of shutting schools. We need to do everything humanly possible (vaccinating, ventilation, testing, including test-to-stay) to keep schools open even in the face of a large surge.

7) Even if Omicron proves to be less severe, don't get lulled: it's unlikely to be massively less severe. If (let’s say) Omicron is 30% less severe but cases go up 5–10x (both plausible), that’s still awful, with far more hospitalizations and deaths than the comparable Delta surge.

8) In your own decision making, on top of weighing personal risk (age, comorbidities) & risk of exposure (activities, masking, case rates in your community, incl. fraction of Omicron), we now need to be more nuanced about level of immunity. It’s no longer Immune: Y/N?

Immunity is now (best > worst):

a) 3 mRNAs + infection (super-immune)

b) 3 mRNAs (very immune)

c) 2 mRNAs OR J&J + mRNA (modestly immune)

d) 1 mRNA OR J&J alone, OR infection alone (minimally immune)

e) No shots AND no infection (totally vulnerable)

9) We all should have paid more attention in 4th grade when we were taught to multiply fractions. Why? Because thoughtful decision making now requires you to multiply (brace yourself):

Personal risk (age, comorbidity) x activity (indoor, crowded?) x # of Covid cases in the region (cases/d/100K) x risk-reduction by you & others (masking, ventilation, etc) x fraction of Omicron in region x your level of immunity (zero to super) x how important activity is to you (visiting kids/grandparents vs. seeing a movie.

Exhausting, right?

10) While some will say "I'm over this," taking no precautions seems too risky. Yes, most Omicron cases will be mild, some severe (especially if high risk), a small number fatal, an unknown percentage will get Long Covid. My vote: try to stay safe until the threat passes or we're more sure of severity.

So what am I doing now? (Context: I'm fairly healthy, mildly overweight 64 y/o, have had 3 Pfizer shots, no small kids or elders at home, moderately risk-averse. I can work from home most days except when on clinical duty, as I am next week).

Would I travel for Xmas? In the US, yes. Omicron is still a minority of cases in most places, planes are safe, and there’s no guarantee next Xmas will be safer. Wear an N95 mask for the whole flight, minimize eat/drink time. To Europe: no, risk of Omicron is too high, and a bureaucratic nightmare to return if you test positive.

Would I dine indoors? Not anymore, even though San Francisco has a very low case rate and an 80% 2-shot vaccination rate. But cases will start climbing soon (& fast) and indoor dining is not worth the risk to me. Outdoor dining: fine for now. Crowded event (sports/concert): not for me at this point.

Would I do indoor shopping or work? Yes, but my rule is to wear an N95 (or equivalent) mask in all indoor spaces unless it's a small group that I'm certain is fully (i.e., 3 shot) vaccinated, and I know all would stay at home if they were feeling sick. Otherwise, my mask stays on in indoor spaces.

Testing? I test myself and my family with any COVID19-compatible symptom (URI, headache, fever, GI). Note Omicron less likely to cause loss of taste/smell. At $12 for a rapid test (ouch), tests aren't as accessible as they need to be. Testing before an encounter makes it far safer, so it's reasonable to test before visiting elderly or other high-risk folks, though I don't test if I'm sure everybody is fully (3 shots) vaccinated. If I was visiting an immunosuppressed or unvaccinated person (incl. a young child), I'd test everybody before gathering.

I hope this is helpful. We're all overwhelmed, exhausted and frustrated by yet another Covid Curveball. I hope you stay safe and sane, and let's hope for a quick surge, a milder illness, and that lots of folks choose now to get vaccinated and boosted.

END OF THREAD

As I remarked already, in this particular thread, Wachter left out all the science behind his reasoning. But, as it happens, I’d already learned about much of that the day before, from a 12-tweet thread by Trevor Bedford on December 16. What caught my eye about that thread in particular, was it referenced King County, WA, where Seattle is located.

Bedford’s thread gives you a good insight into the mathematical-thinking reasoning he employs to reach his conclusions. Eight of this twelve tweets require the reader to look at a graph or chart and extract the requisite information. (One thing the pandemic makes abundantly clear is the crucial importance of having a substantial coverage of data science in K-12 mathematics education. As a skillset that everyone should possess in today’s world, it’s way more important than Algebra 2 or Calculus, and to my mind if there’s a “pick one” choice to be made, it’s a no brainer to go for data science. Ask yourself, “Which one might save your child’s life?”)

The argument Bedford presents rests on a foundation of empirical field-science, laboratory science, and data science, but his reasoning takes place at a higher level that involves issues of human psychology, social science, and politics. That’s typical of mathematical thinking.

[TRIGGER WARNING: Normally, the political issues of managing a pandemic would not be controversial. Journalists who wrote about the polio epidemic back in the 1950s were not attacked. But when you read the threads I will cite in this article, if you continue on to the reader comments that follow, you will find they can become quite heated, sometimes including ill-informed, incendiary remarks (in many cases based on an inability to properly understand the original thread). In fact, simply by posting this month’s essay, I am being “partisan”, since in this country one of our two main parties has adopted a strong anti-science (and by extension anti-mathematics) position. I’m just going to focus on the mathematical thinking here, but in so doing I expect to be attacked, and possibly – though in my case, in this venue, I think unlikely – receive death threats. In any case, venture into the responses in those expert threads knowing what to expect.]

Sometimes, one of the experts deliberately enters the political arena; not to do so would be a clear scientific dereliction of duty. Bedford did exactly that in a June 6, 2020 thread, soon after the George Floyd killing, when it was unknown if large, open-air rallies would result in a COVID-19 surge. It’s another excellent illustration of mathematical thinking. Notice that Bedford is not afraid to put forward some statements explicitly as “best guesses.” The truth is, there’s often a lot of guessing going on when you are at the front-edge of science – and mathematics, of course. (The Riemann Hypothesis comes to mind.)

Bedford’s December 20 thread, where he looks into the data supporting the distribution of booster shots, provides another superb example of (data-driven) mathematical thinking. Remember, this is not “published research”; what we are witnessing is science and policy making happening in real time, in a domain that massively impacts every one of us. The work is “peer reviewed”, for sure; we are witness to that very process! Making the messy process of formulating scientific hypotheses and reaching scientific consensus visible to all in real time is, I suggest, a huge positive outcome that comes from a real-time tool such as Twitter.

[Incidentally, the MAA saw that potential very early on. In 2009, not long after Twitter was launched, the MAA ran a workshop in which we looked at how to make use of the new platform, organized by Ivars Peterson, in which I took part, along with Past MAA-President Paul Zorn, among others.]

Before I leave Wachter and Bedford, let me direct you to Wachter’s 25-tweet thread of December 22, which provides an update to his December 17 thread I led off with. It shows just how much things can change in just five days when you are in the middle of a pandemic. We get to see, close-up, in real-time, as leading scientists try to stay ahead of the virus. [And yes, he becomes “political” in some of the threads. In the present environment, being scientific or presenting data is viewed as “partisan” by those who reject science and its underlying mathematics. That’s now just a fact of life.]

In addition to his work as an evolutionary biologist at the University of Washington, Carl Bergstrom is a talented photographer of birds (hence the twitter photo), and co-author of the book Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World

Another expert I learn a lot from is the University of Washington’s Carl Bergstrom. His tweets vary considerably in the degree of detail he provides, but sometimes he dons his professor’s cap and provides a lesson in how to present and understand the ongoing science, as he did early on in the pandemic in America, with an 18-tweet thread on April 13, 2020, that looked at how best to present and understand data and graphs. (An issue I have taken up in a couple of Devlin’s Angle posts during the pandemic.) As Bergstrom shows, Twitter can be used as a medium to deliver a lecture!

The benefit of doing so on Twitter (as opposed, say, to giving a course on Coursera) is that it makes it available to the people who demonstrably need it to follow the various tweets and threads from folks like Wachter and Bedford, and moreover it can be done with the very latest data as an example. (Bergstrom too feels the need to comment about the unavoidable “politicization” that accompanies talking about science and data when the very use of science itself has been politicized.)

Finally, let me give you examples of the remaining two of my Top Five experts who make their work accessible to the world in real time.

First up, Eric Topol, of the Scripps Research Institute in California. Like Bergstrom, Topol sometimes decides there’s a need for a lesson to help non-experts (like me) better understand what is going on. His 5-tweet thread on November 28, 2020, posted just when the first mRNA vaccines were coming out, provided a succinct crash course on the history and significance of that development. Reading that at the time, and re-reading it just now to write this post, really brought out for me just what a phenomenal scientific achievement the production of those vaccines was.

The two Erics, Eric Topol and Eric Feigl-Ding, complete my personal Top Five Twitter-active epidemiology experts who together provide us with a privileged, highly informative ringside seat into the making and application of science

Finally, American Public Health Scientist Eric Feigl-Ding leans towards denser, more detail-filled tweets and threads, that are usually heavy on the data science. His posts surely fall well outside the interest or capacity of many who follow Wachter or Bergstrom, but for regular Devlin’s Angle readers, they can be hugely informative, and for the guy who writes Devlin’s Angle they also provide a superb illustrations of mathematical thinking.

For an example to include here, I started by looking to see what he had just posted when I was composing this post (on December 23) and the first thing that came up was a 14-tweet thread that provides an excellent example. I did not have to look any further. Check it out. It’s like being in a university research seminar, and a fascinating one at that.

Feigl-Ding’s declared topic is to compare the new Omicron variant with the older Delta one, but note in particular how far he ranges into areas of public policy.

And yes, he too does not shy away from stepping on people’s toes, when he believes misguided or maliciously-intentioned administrative decisions are made. The stakes are far too high for any leading scientist to remain quiet and hope everything will simply work out okay in the long run.

And there you have it. The five experts I have mentioned are by no means the only ones you will find on Twitter, nor are they the only ones I follow. But they do all provide excellent examples of mathematical thinking in action. I wish you stimulating reading. It may even save your life.

#Science_in_Public